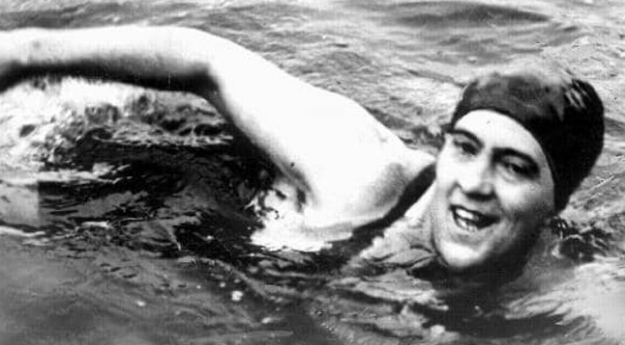

Sarah ‘Fanny’ Durack - Herstory Ireland's Epic Women | EPIC Museum

The Irish-Australian who won the first women’s Olympic swimming medal and who broke a total of 12 world records

Born to Irish emigrant parents in Australia, Fanny Durack was lucky that she was not born in Ireland. If she had, she may not have had the opportunity to become a champion. In the same week that Fanny Durack won the first gold medal in women’s Olympic swimming, four Irish suffragettes went on trial for breaking windows in Dublin. If her parents had stayed in Ireland, would Fanny Durack have been at the Olympics or would she be on the streets fighting for women’s rights too?

From the 1890s onwards to 1900, Australian states had slowly been rolling out votes for women. In contrast, in Britain and Ireland, the vote was only won in 1918. However, there were still significant amounts of discrimination and sexism as regards to rights of Australian women, there was still much to be done for the cause of women. Fanny Durack made her own statement about what she could achieve as a woman, not just by competing professionally as a swimmer, but also with what she was wearing doing so.The fascinating thing about Fanny Durack is that she was mostly a self-taught swimmer. Yet by the time she was 17, Fanny Durack won her first state swimming title. Durack clearly had a natural knack for swimming, an athlete who was born at just the right time to shine. For the first time ever in the history of the Olympics, the 1912 games were to allow women to compete in swimming. Women had only been allowed to participate in the Olympics since 1900, swimming and diving had only been added in 1912. 2,408 athletes participated in the 1912 Olympics and only 48 of them were women. That means only about 2% of those who competed in 1912 were women.

The Australian public were endlessly proud of Durack. A campaign was started to get her to the 1912 Stockholm Olympics and numerous local and international publications wrote about the “water-nymph” who should represent Australasia in the Olympic Games. However, women were banned from competing in events where men were also present. By this point Durack had 56 medals and 100 trophies to her name. As The Barrier Miner put it, “If this formidable array is not a record that Australia should be proud of in one of her daughters, then there is no such thing as national pride… There can be little doubt that she is the best lady swimmer in Australia.” Thanks to public appeal, along with this “formidable” record of hers, the ban was lifted and Fanny Durack was allowed to compete in Stockholm.

Arriving in Stockholm, Durack shocked the crowd by donning a sleek, close-fitting swim suit instead of the modest and ‘appropriate’ woolen swimsuit. Not caring whether her outfit was ‘decent’ enough for a woman to be wearing at the time, Durack argued that the heavy clothing she was encouraged to wear had “as much drag as a sea-anchor”. While suffragettes were brewing a revolution in England and Ireland, Fanny Durack was participating in her own rebellion against societal standards for women at the Olympics when she wore that suit for the 100m freestyle event. And it paid off. She became the first woman to ever win the Olympic gold medal in swimming, not just for Australia but in the world.

Between 1912 and 1918, Fanny Durack broke 12 world records. Just a week before Durack was due to travel to the 1920s Antwerp Olympics, she was stricken with appendicitis. She had an emergency appendectomy and subsequently contracted both typhoid fever and pneumonia. By 1921, due to her health, Fanny Durack retired from competitive swimming in January 1921. She dedicated herself to coaching children and lived until 1956. Fanny Durack was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1967. She had a massive impact on the perception of women athletes, not just in Australia, but across the world. Fanny Durack was a champion who very much blazed a glorious trail for every female Olympians who came after her.

Illustration by Szabolcs Kariko as part of Blazing a Trail exhibition at EPIC in collaboration with Herstory and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The exhibition, launched in November 2018, runs again at EPIC at various dates from January - March as part of a series of special events at EPIC as part of the Herstory 20/20 project focusing on Ireland's epic women. Click here to find out more about our events as part of Herstory.