Eva Gore-Booth - Herstory Ireland's Epic Women | EPIC Museum

Gore-Booth, the quiet sister of Countess Markievicz, who became an icon of suffrage, trade unionism, nationalism and LGBTQ+ defiance

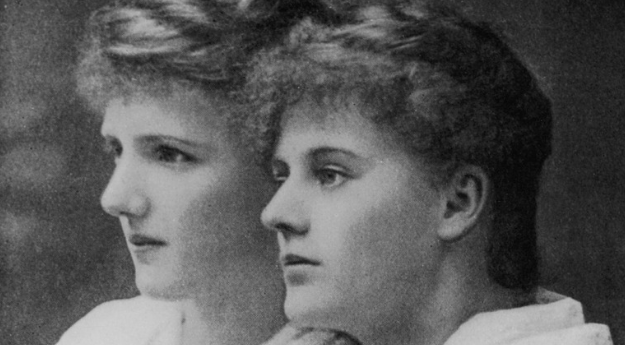

What can be said of the poet, suffragist and Irish nationalist Eva Gore Booth? You may not have heard of her, but you have probably heard of her older sister Countess Constance Markievicz. Yet, Eva’s artistic and social contribution is as important as her sister’s, if not more so. So why is she overlooked in history?

Eva Gore Booth was the third of five children born to the aristocratic family of Sir Henry and Lady Georgina Gore-Booth in Lisdell, Co. Sligo. Her family were socially conscious despite, or perhaps because of, their wealth and reputation. Her mother started a needle working school in Lisdell, so that the women in the town could earn an independent wage. Their mother’s social endeavours is probably what inspired both Eva and Constance in their campaign for suffrage and Irish Independence throughout their lives.

The two eldest Gore-Booth sisters could not have been more different, yet they were close friends for the entirety of their lives. Constance was wiley, strong-willed and vocal whereas Gore-Booth was a lot quieter, graceful and empathetic. According to their governess, Eva was “always so delicate” and often let her older sister overshadow her. She was the type of person who didn’t mind being quietly in the background, but that by no means made Eva a passive person. She was deeply passionate, a fact that is probably most evident in her poetry and she was a fierce campaigner for women’s rights, worker’s rights and animal rights throughout her life. As Stephen Hawking once put it, “quiet people have the loudest minds”, and this was certainly the case for Eva Gore-Booth.

Eva Gore-Booth fell in love with folk-telling and Irish lore and became a poet when her sister left for France to study art. Eva herself travelled, although her home was still in Sligo. That was until she met English suffragist and social justice campaigner Esther Roper. Whilst travelling in 1896, Gore-Booth fell ill and moved to Bordighera in Italy to recover. It was here that she met Esther Roper, who was also recovering from an illness. The two fell hopelessly in love.

Gore-Booth returned to Sligo and Roper to Manchester in 1897. They were barely apart for a few months when Gore-Booth uprooted her aristocratic life to live in Manchester with Roper. I wonder what her family thought, Eva dislocating herself from her comfortable family home to follow her lover across the Irish Sea? Certainly, it had no effect on Constance’s relationship with her sister. Constance was very fond of Roper too, writing that “Esther is wonderful, and the more one knowns her, the more one loves her”. In a time where being a homosexual was a punishable crime, Eva and Esther defied societal norms by being openly devoted to each other.

Roper and Gore-Booth came from completely different worlds. Roper’s parents were working-class Irish immigrants, her father was a factory hand who moved to England during the industrial revolution. Roper was a highly intelligent child and became the first woman to graduate from the University of Manchester. Her compassion for working class women and her activism for the causes of suffrage and labour rights further inspired Gore-Booth to become involved in those social causes herself.

During her brief return to Sligo, Eva called the first women’s suffrage meeting in a local hall in December 1896. Though the meeting was scoffed at by new outlets at the time, Eva was far from deterred from supporting the cause of suffrage. An article in Vanity Fair stated how the “three pretty daughters of Sir Henry Gore-Booth are creating a little excitement… supported by a few devoted yokels”, never anticipating how the Gore-Booth sisters would create much more than a “little excitement” in society.

Esther Roper lit the fire in Eva Gore-Booth that ignited a life-long devotion to social causes. Eva’s poetry is often politically charged, poems like The Anti-Suffragist being a short but particularly scathing commentary on those who turn a blind-eye to injustice. Though Eva was living abroad, she never forgot her ties to the Ireland, being outspoken in favour of Irish Independence. When Constance Markeivicz was captured in 1916, Gore-Booth and Roper smuggled themselves into a Dublin on lock-down to visit her in Kilmainham Gaol. Following her release from Aylesbury Prison, the couple met her and brought her back to their London home at 33 Fitzroy Square, which became known as a hub of Irish Nationalism in London.

In the 1920s, it was found that Eva Gore-Booth had terminal colon cancer. She begged Roper to keep it from Constance and it was Roper’s Brother and Roper herself that cared for Eva in her final days. She passed in 1926, the news coming as a shock to Constance, who was too bereft to attend the funeral. She herself died a year later in 1927, arguably of a broken heart, though not before writing in a letter to a friend that she was “so glad that Eva and [Esther] were together. So thankful that her love was with Eva until the end”. Esther Roper died in 1938 and is buried with Eva Gore-Booth in London. The inscription on their headstone is “Life with Love is God.”

Eva Gore-Booth was an icon of suffrage, of trade unionism, of nationalism and of LGBTQ+ defiance in an age of unacceptance. Though she may be the lesser-known Gore-Booth sister in Ireland, she is highlighted and honoured in the Blazing a Trail: Lives and Legacies of Irish Diaspora Women exhibition, cementing her place in history.

Sonja Tiernan Bibliography

Sonja Tiernan, Eva Gore-Booth: An Image of Such Politics (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012)

‘Challenging Presumptions of Heterosexuality: Eva Gore-Booth, A Biographical Case Study’, Historical Reflections, 37:2 (Summer, 2011), pp. 58-71.

‘”Engagements Dissolved”: Eva Gore-Booth, Urania and the Radical Challenge to Marriage’, in Tiernan and Mary McAuliffe, eds., Tribades, Tommies and Transgressives: History of Sexualities: Vol. 1 (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2008), pp. 128-144.

Illustration by Szabolcs Kariko as part of Blazing a Trail exhibition at EPIC in collaboration with Herstory and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The exhibition, launched in November 2018, runs again at EPIC at various dates from January - March as part of a series of special events at EPIC as part of the Herstory 20/20 project focusing on Ireland's epic women. Click here to find out more about our events as part of Herstory.