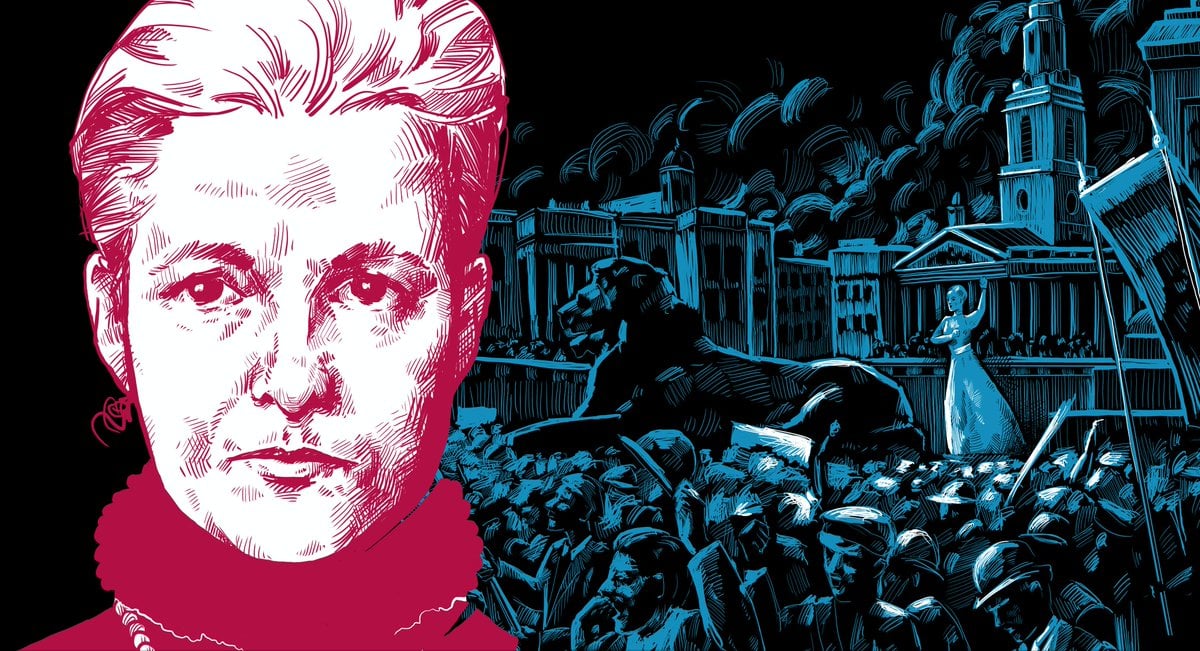

Annie Besant - Herstory Ireland's Epic Women | EPIC Museum

The trade unionist, socialist, and later Indian nationalist who was the first woman to endorse birth control

Annie Besant was an undeniably fascinating woman. Coming from a staunch religious background through her marriage, Besant became an atheist championing birth control, and then a theosophist advocating for Indian Nationalism. So how did a woman, so apparently dedicated to her cause, bounce from one ideology to another and to another again?Besant was born Annie Wood to Irish parents living in London in 1847. The Besant name came from her husband, Reverend Frank Besant, whom she married at the tender age of nineteen. Despite keeping her husband’s name throughout her social prominence and making it her own, by her admission they were an “ill-matched pair”. Her husband was controlling and, despite the fact that they had two children in 18 months, the couple became somewhat estranged early-on in the marriage. She took up writing in 1868, hoping to make a living out of it, and was horrified to realise that as a married woman, her husband took control of all of her earnings. This marked the beginnings of her interest in activism, as she herself was a victim of the sexist and restrictive laws regarding women at the time.

The turning point in her life came in 1871, when she almost lost her baby daughter to whooping cough. She began questioning her faith, something that angered her pious and conservative husband who presented her with an ultimatum- “Hypocrisy or Expulsion”, as Besant later put it. He demanded that she take communion regularly in front of his congregation, failing that she would be excommunicated from the church and from his life. She agreed to a legal separation from the Reverend, moving to London with her young daughter. Freed from the shackles of an unhappy marriage, Besant dedicated her life to activism.

Becoming a journalist with the secular periodical The National Reformer, Besant was able to make an independent wage. She became a vocal critic of religion, particularly of the Church of England, and became outspoken about the pressing social issues of the time. Besant was put on trial under the Obscene Publications Act for co-publishing The Births of Philosophy which outlined an argument in favour of the use of contraception. She was one of the first women to publically endorse the use of birth control, which she vehemently defended at her trial. This would spell disaster for Besant, however, as her husband would use her stance on contraception against her to take full custody of their daughter, claiming that Besant was an “unfit mother”.

She never regained custody of her children, which all but broke Besant’s heart. In spite of this, the children continued to be influenced by their mother’s beliefs and the two became involved with Theosophy later in life. Up until 1889, Besant was an adamant atheist. However, in meeting Helen Petrovna Blavatsky, the Russian co-founder of the Theosophical Society, her viewpoint changed almost overnight. Perhaps it was Theosophy’s female leadership that drew Besant in? In a time where so many women had a complete lack of control over their lives, Theosophy gave Besant and so many others a sense of power and freedom.

Besant became the head of the Theosophical society upon Blavatsky’s death in 1891. She came to Madras in India in 1893 were she would spend the rest of her life. She never forgot her strong social morals, she was a strong component in educating poor Indian youth and was an advocate and campaigner for Indian nationalism. She was the first female leader of the Indian National Congress in 1917 but her influence on Indian politics dwindled after she was interned for the cause between May and August in 1917.

In 1933, Besant died at Adyar at the age of 83. Tributes were paid all across the world from Theosophists, feminists and Indian nationalists alike.

Illustration by Szabolcs Kariko as part of Blazing a Trail exhibition at EPIC in collaboration with Herstory and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The exhibition, launched in November 2018, runs again at EPIC at various dates from January - March as part of a series of special events at EPIC as part of the Herstory 20/20 project focusing on Ireland's epic women. Click here to find out more about our events as part of Herstory.